Is it still a wonderful kind of day?

Does race matter in children's TV? It’s a question with an easy answer: representation matters, especially for children. Growing up, kids want to see a version of themselves on screen, a version that intersects with at least a few aspects of their lived experiences. Attributions of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ characters are often framed around accents and skin-colour when it comes to children’s cartoons. A study published in Salon shows that there is a strong need for representation for Asian and Black populations in American media. The way voices are portrayed matters for this reason as well.

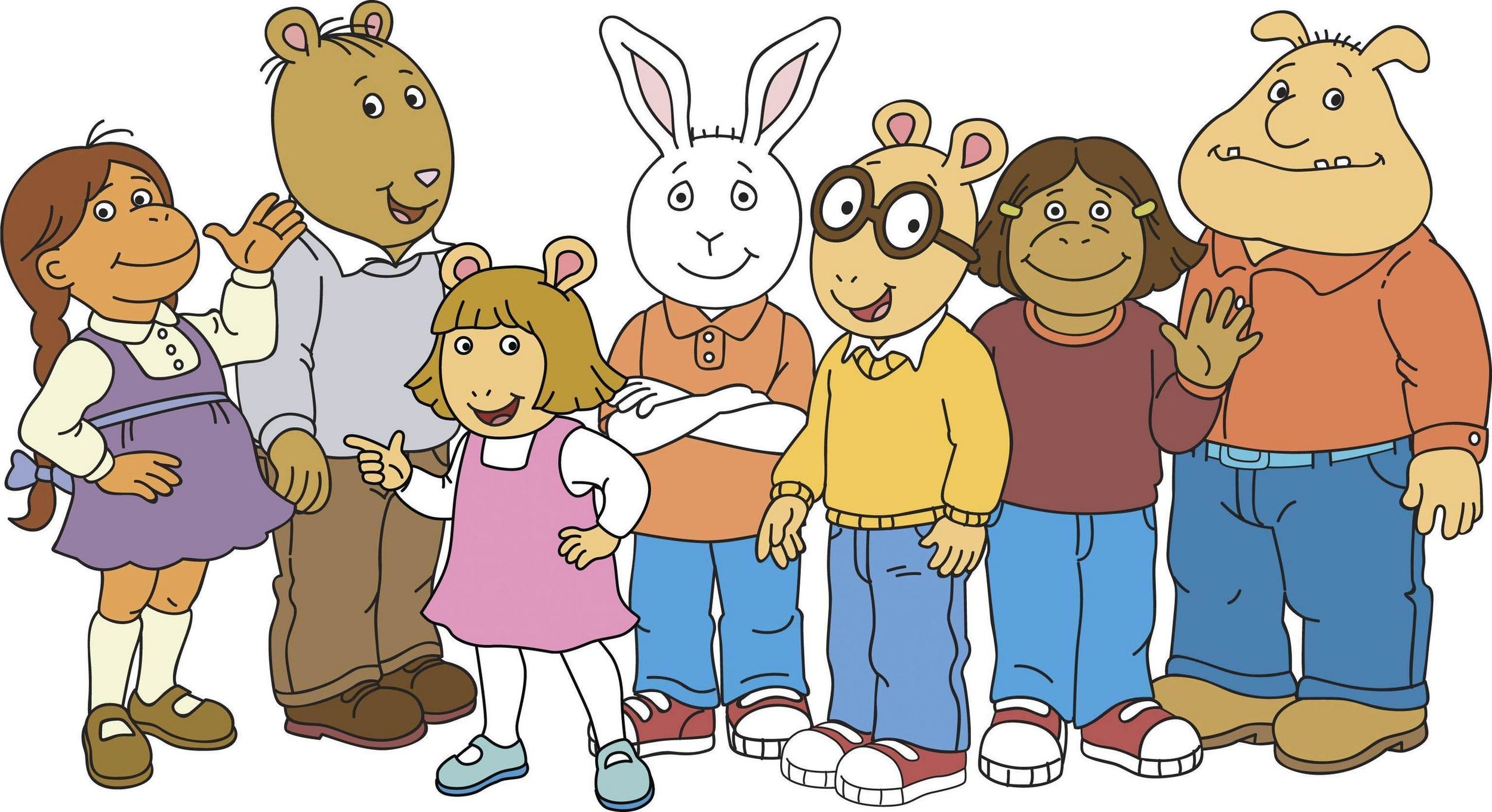

My favourite show growing up was Arthur. The characters were to true life, experienced the regular ups and downs of childhood, and the show's creators actually addressed a lot of important issues like dealing with cancer, environmental degradation, single-parent homes, disabilities, and mental health. It continues to do that in 2019, with the recent development of Mr. Rathburn’s queer storyline and gay wedding. On a smaller scale, I recently watched an episode where sociological sampling methods were discussed at length, and invited a conversation about transparency when it comes to polls and data analysis. But what does a seemingly “deep” show like Arthur have to say about race?

Race only comes up when it has to. As the characters are all anthropomorphic , it seems there’s no need for racial distinctions. Yet, they exist. Binky Barnes’ adopts a Chinese daughter for instance, Mei Lin, and she appears to be visibly Asian, down to her hairstyle and outfit, both traditionally Chinese. The Reid’s neighbours, the Molina family, are Ecuadorian. Season 6 introduced the family as new members of Elwood City, bearing strong accents and dark brown skin. They talk about their traditional foods and teach Spanish words to D.W. and her family. If we know the race of characters who are supposed to be Chinese and Ecuadorian, then why don’t we know the race of the main cast of Arthur and his friends?

Here me out while I bring up a theory some may find disgruntling. I’ve always thought Francine Alice Frensky was half-brown. South Asian, Carribean maybe, but I never thought she was white. The same goes for the Brain (who I thought was Black) and Arthur (who I thought was also unspecifically mix-raced). But Francine was the character I connected to most myself because she’s from a low-income family, her justified anger is misunderstood as pushy or insensitive, and she’s pushed around by her best-friend (Muffy Alice Crosswire) who is the definition of white privilege. She also wears a sweater and jeans all the time, just like me. The first episode where Francine is the main character (Season 1, Episode 1.5) revolves around her hair being criticized by Muffy. In the bathroom a few days before photo day, Muffy runs a comb through Francine’s and it sticks there, supposedly caught in her tangles. It reminded me of my hair, it’s coarse texture, the way it’s so easily knotted and the way it was criticized by my white friends. Muffy tells Francine that she can look just as good as her if she changes her appearance. This is wrong on many levels, and Francine does eventually come to this realization. However, it takes a lot of changes to her hair and clothing before she accepts herself outside of Muffy’s criticism.

To be fair, most of Marc Brown’s characters were created in the 1990s without race in mind, and they are a lot older than the discussions of identity politics the modern day Arthur holds today. So was I just looking for representation that wasn’t there when I was younger? Probably, but I’m not the only one. After reading Sarah Hagi’s piece for Vice, “All Your Favourite Cartoon Characters Are Black,” I realized I am more relatable than I thought. “Why would they [white people] need to understand the need to identify with non-human characters by attributing them to a race?” Hagi writes, “When it comes to entertainment, white people never have to imagine themselves as being the stars of movies or shows because they always already are.” The thing about anthropomorphic characters is that they can kind of be whoever a child’s brain wants them to be, unless they are explicitly defined. That’s not necessarily a good thing. Representation shouldn’t mean inventing an identity for characters that may or may not look like you, but it has for a long time, and still does in many areas of the media.

It should be noted for context purposes that Marc Brown voiced his opposition to Trump before the 2016 election. According to Huff Post, He also hasn’t dismissed the idea that Francine could be a lesbian, and adovocates for all children to be able to see themselves in his distinct spectrum of characters. "Art reflects life. Life reflects art. And I think that kids need to see what's happening in the world,” said Marc Brown in a 2019 interview with CBC after the premiere of “Mr. Ratburn and the Special Someone,” a landmark episode for queer visibility in kids TV.

A show like Arthur has become a kind of a social phenomenon, in part because of it’s reaction memes like the Arthur-fist, and because of its ability to become an object of cultural studies. It has the ability to extend across generations and remain relevant through tumultuous political times. Chance the Rapper even did a cover of Ziggy Marley’s “Believe in Yourself,” which still serves as the upbeat theme song of the show.

The universe of Arthur represents the Jewish community with Francine’s family, Catholicism in the Reid family, some Chinese culture with Mei Lin, touches on Ramadan with Arthur’s pen-pal Adil, and Ecuadorian culture with the Molina family, so those small representations should act as an open door to delve into more identities and address other intersectional issues. Is the show going to address Islamophobia, a sentiment that has wracked the United States since 9/11, when Arthur was at its prime? What about systematic anti-Black racism, one of the worst plagues on civilization across the world? Let’s see some more queer content, trans and non-binary children, Indigenous children, and maybe more coverage of mental healh issues beyond George’s stage fright and Fern’s measly episode about depression. My love for this show is boundless, and I would love to see more depth and breadth of characters because every kid deserves to see themselves on screen. The show has it hit a new sweet spot with a generation of kids that are more curious and deserving of intersectional knowledge than ever before. It is telling that a show like this still has a lot of Gen-Z fans. It’s been respected for generations because of its ability to touch so many communities. It has told thoughtful and intricate stories that have often been overlooked in children’s television. And the best thing about it? There’s still time to create new ones.